Why Build Anything at All?

If you genuinely care about anything and want to avoid sounding like a mad scientist when you talk about it, I highly recommend you start forming your thoughts and efforts into digestible pieces of content. Engineers are notoriously horrible with communication, but we care and want to build something that truly works. To make something work, then, means to make something that works for people. But, if no one can understand what we are doing or why, we haven’t actually made anything that works. We’ve made something else, which is fine; there are many things we can do for ourselves or our own benefit, and the world doesn’t have to understand them completely. Instead, making something that works starts with correctly identifying real people’s issues. We have to spend time talking to them about their difficulties and perspectives and listen when they tell us what they need or what we aren’t providing. If we do all this and still fail, it’s okay; you were just trying to help.

If you want to reach the people who need you and your skills the most start sharing and they will come. Many companies have seen the benefits of opening up their private works and allowing people to participate in the systems they rely on, like Google’s Chromium

or

or Red Hat’s Podman

. Similarly, I hope sharing what I do reaches an audience of individual personal computer users who could benefit, while acknowledging that many real people can’t even make it here. Even if no one reads these paragraphs, writing them organized my thoughts about website technology so at least I can understand what I am doing and why. If you don’t follow the rest of this guide to make a website to host your content, I highly recommend building some other habit of explaining what you do, even if you’re literally talking to a wall or a mirror, so if someone ever does ask you for help; you’ll be ready. Now that you and I both know why we are here, let’s get into it:

. Similarly, I hope sharing what I do reaches an audience of individual personal computer users who could benefit, while acknowledging that many real people can’t even make it here. Even if no one reads these paragraphs, writing them organized my thoughts about website technology so at least I can understand what I am doing and why. If you don’t follow the rest of this guide to make a website to host your content, I highly recommend building some other habit of explaining what you do, even if you’re literally talking to a wall or a mirror, so if someone ever does ask you for help; you’ll be ready. Now that you and I both know why we are here, let’s get into it:

Requirements

A computer

that can run

that can run Deno. Deno is a software written in

Rust, so there are some unofficial builds too. If you aren’t running Mac, Linux or Windows I recommend looking around.

Rust, so there are some unofficial builds too. If you aren’t running Mac, Linux or Windows I recommend looking around.An internet connection 🛜. In America, internet connections are paid services provided by organizations like

Xfinity or Verizon. To connect you to a computer

located across the world

located across the world  , these organizations work with larger networks that manage global connections, like undersea cables and satellites.

, these organizations work with larger networks that manage global connections, like undersea cables and satellites. (optional) If you want others to be able to access your website, you will need a

GitHub account.

GitHub account.

Exploring Website Technology

2 Kinds of Software: Servers & Clients

All websites and website technologies, of every language and scale, boil down ![]() to 3 main ingredients. These ingredients are just different kinds of

to 3 main ingredients. These ingredients are just different kinds of ![]() text we store in files:

text we store in files:

JavaScript nologo: Code that the browsers can run. Chrome runs JavaScript files using Google’s open-source V8 JavaScript Engine. To execute a

.jsfile from your command line, you’ll need a runtime--software that reads and runs code. The most popular JavaScript runtime, Node.js, and what we will use today, Deno, are also built on the V8 engine. After installing, to run the code written inserver.js, for example, you would have to do$ deno server.js, similar to how Python code is run.HTML

: This language describes to browsers what to draw in the window canvas. It contains the content and the ordering of paragraphs of text, images, links, boxes, and all the visual elements in the browser window. The JavaScript code can also read and change the window’s HTML: this is how most meaningful visual content changes and code interactions happen.

: This language describes to browsers what to draw in the window canvas. It contains the content and the ordering of paragraphs of text, images, links, boxes, and all the visual elements in the browser window. The JavaScript code can also read and change the window’s HTML: this is how most meaningful visual content changes and code interactions happen.CSS

: This is a set of properties you can use to modify the display of HTML elements. To match my HTML examples above, you could set text font, images opacity, links color, and boxes size. The same HTML can look significantly different depending on the

: This is a set of properties you can use to modify the display of HTML elements. To match my HTML examples above, you could set text font, images opacity, links color, and boxes size. The same HTML can look significantly different depending on the .cssstyle file sent with it. If you didn’t adequately receive the.cssfile when visiting a site, all the text could be black on the left, and the background would be white, depending on the browser’s CSS defaults. You may have briefly witnessed this as a slow site loads or if your connection was interrupted before getting the CSS.

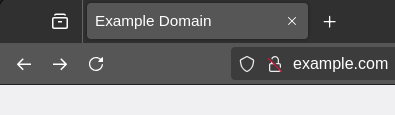

The boiling down gets complicated as the three ingredients start to mix. Browsers are large softwares; web technologies, and as you’ll see, are up to so much of this boiling automatically under the hood. Let’s start with a minimal example. I’ll assume you’re using a browser, so let’s type example.com into the address bar:

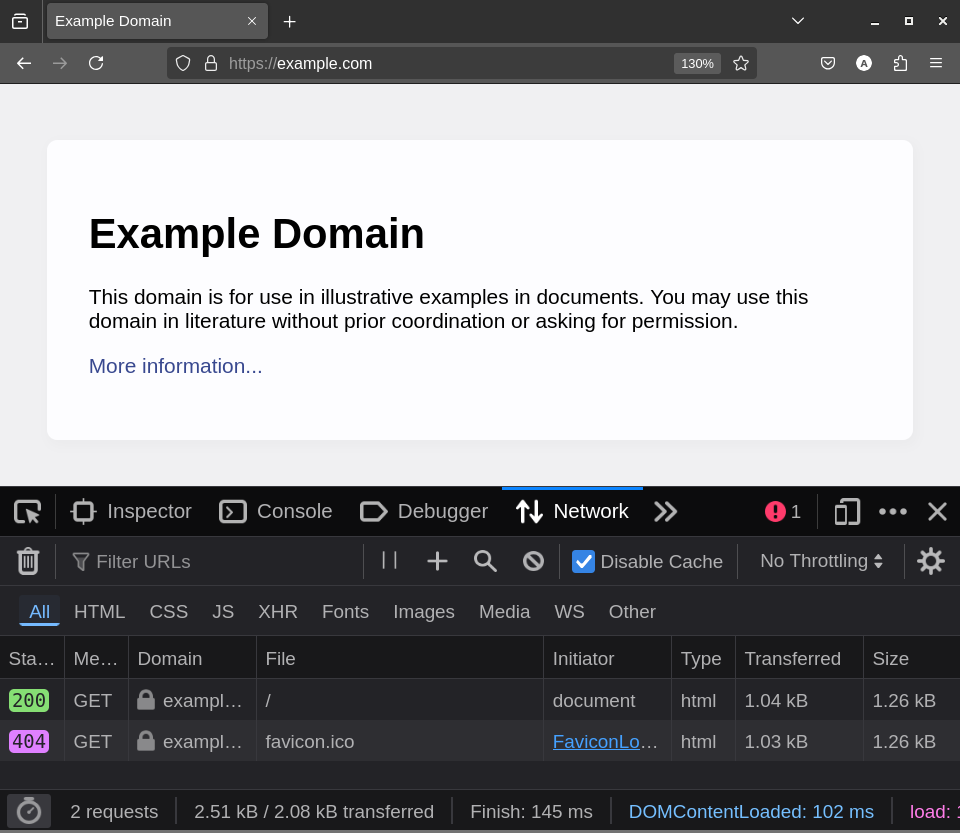

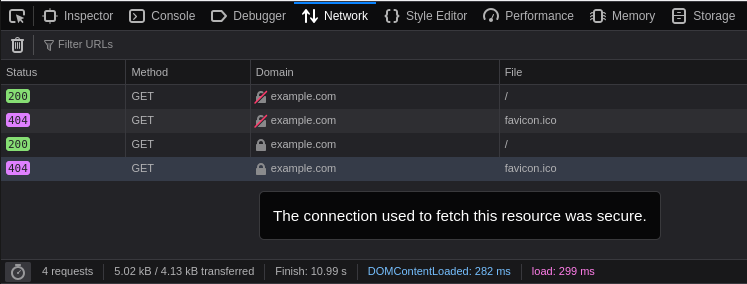

Network tab

After I hit ↵ Enter, my browser requests the / HTML file to display in its main window and favicon.ico to fill in the icon in the tab title bar. In the image above, my browser’s favicon request 404s (file not found), but the / response is a document of type HTML. example.com is a minimal example, so it doesn’t have a favicon; without it, the main page will still load fine since / did not 404 and instead was "found".

A New Dish

Next, let’s examine how intense relationships ![]() between website technologies and the three main ingredients can get. Our minimal

between website technologies and the three main ingredients can get. Our minimal example.com has sent 1 HTML file:

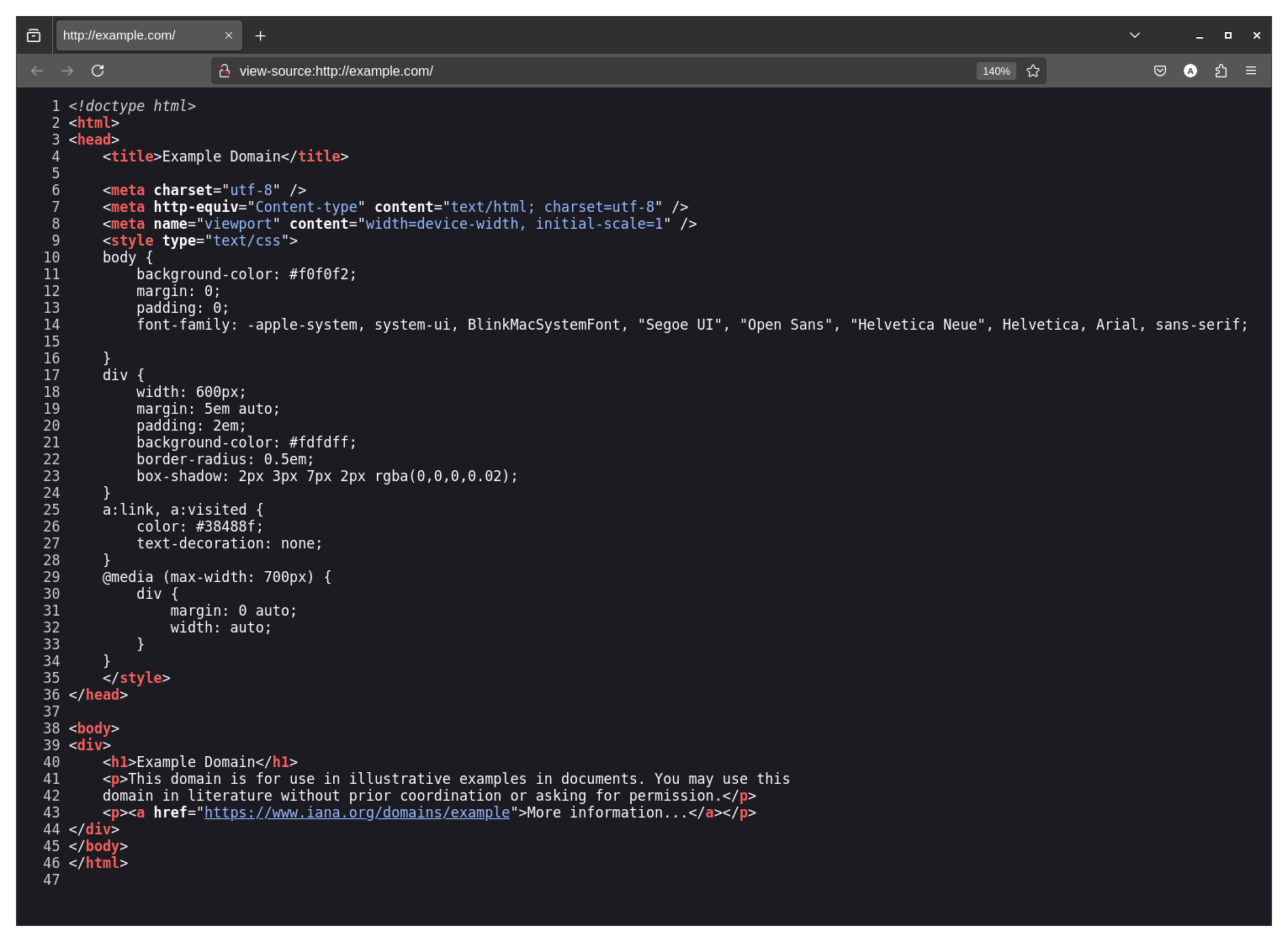

view-source:https://example.com/

On line 4, we have an HTML <title> tag which modern browsers read and then render as the tab name:

example.com Tab Name with no favicon

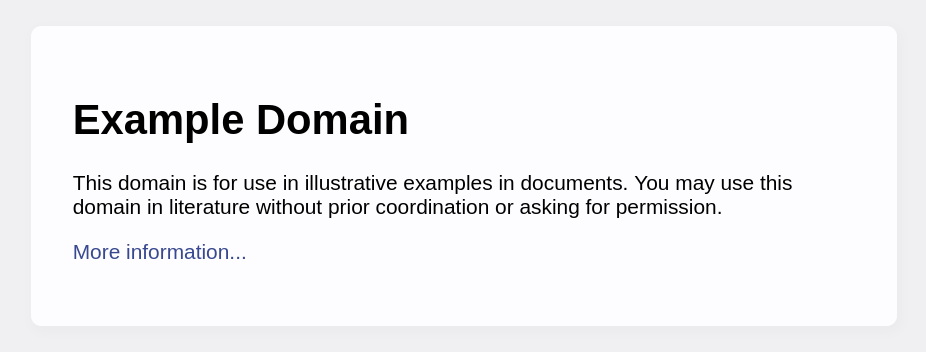

On line 9, there is an HTML <style> tag of type text/css, meaning the next block should be read as an inline .css file. On line 14, the inline CSS sets which font the browser should use to display text in the <body> tag:

example.com Styled Content

Using the browser Developer Tools, I can delete some of what they sent to show you what a world with no CSS could look like:

example.com No CSS Alternate Universe

We are witnessing our first most basic twist ![]() on the ingredients: The

on the ingredients: The ![]() text stored in the file is now of 2 languages that work according to 2 different standards stored in different ways on 2 computers. I don’t suppose you’ll find

text stored in the file is now of 2 languages that work according to 2 different standards stored in different ways on 2 computers. I don’t suppose you’ll find example.com’s index.html in your Downloads folder, and example.com’s server system could be a mouse trained to jump on a keyboard to compose HTML and CSS and pack it up as an HTTP response. Most websites don’t employ mice and instead use software to listen for requests and craft & deliver responses. In fact, example.com tells us its server software is ECAcc (dcd/7D5D) in its response headers, a set of metadata server softwares can send along with responses. ECAcc (dcd/7D5D) is a CDN made by Verizon. The best resources for learning how to use the three main ingredients and their standards are either W3Schools or, my preference, Mozilla. Mozilla also covers new ![]() web technologies like WASM and WebGL

web technologies like WASM and WebGL

In the following sections, we will see how to:

- Download

Deno and

Fresh and use them to create a website and make it accessible over the internet (skip to section).

- Use Deno and Fresh as the software to generate the HTML files and send them along with JS code to run in the browser as a response to build a cohesive website (skip to section).

Wait, It’s All Computers & File Systems?

example.com is like a name for a computer that my browser can use to find and connect to over the internet. The software running on that computer, serving the file, is considered; The Server. Our greedy, needy browser software requesting so many files would be The Client. Server & Client are sometimes used to refer to the machine, causing confusion with server computers, which are computers optimized to run server software. As we move into a computing landscape where most computers are running server and client software, I suggest, when needed, we use Host when referring to computers running server software and Guest for computers running client software.

Most servers send /index.html by default when a file is not specified: /. You can see this is true by going to example.com/index.html or google.com/index.html, and if you want to go on a tangent try google.com/robots.txt. The idea, traditionally, is that browsers are like remote file system browsers, but the files we are sharing have advanced. If you have  Python installed, you can easily see your own computer’s fs in your browser by trying:

Python installed, you can easily see your own computer’s fs in your browser by trying:

$ python3 -m http.server # 8001 # <- uncomment if port in use

By visiting the link provided by Python in your browser, you’ll be able to navigate the folder in which you ran the command. This command starts a program on your computer that listens for HTTP requests on port 8000. This program would be considered a server, which isn’t surprising since we ran Python’s built-in http.server module using the -m option. This Python program serves the files of the folder it was run in, and its HTML webpage response looks like a file browser UI. A port is like an extension to a computer name where that computer is listening for data that follows a specific protocol. HTTP and HTTPS are different protocols for transferring website files; they define how the HTML and other files should be asked for and packed up. Most client software delivers HTTP requests to port 80 by default if no ports are specified in the request. Multiple softwares can be listening on one computer, so thus we have Ports so that 1 machine can listen for many protocols on different ports. Secure websites redirect HTTP requests to port 443, and secure browsers stick to HTTPS whenever possible, effectively upgrading the security before receiving website content.

Other than 80 and 443 for website content, there are many default ports that other non-website servers listen on, indicating that there are many kinds of server softwares and protocols for them. For example, there are default ports for 22 for SSH, which serves a remote shell, and 53 for DNS, the system that turns example.com into a real computer address;. Hence, it serves IP addresses. Client software knows how to properly request and use this information, so any other computers running browsers on the same network as your computer running the Python server can connect to your computer using the port you opened above. To prevent this, you must either use a firewall to block requests or just stop serving and close the http.server by sending Ctrl+C. Check out this section of the vpn/dns post that covers setting up firewalls.

example.com HTTP (first 2 requests) vs. HTTPS (second 2 requests)

You can see this by visiting the insecure example.com:80/ or example.com:443/ and seeing that sending an HTTPS request to port 80 would fail since that port is expecting HTTP traffic: https://example.com:80. Since that link cant be visited in my browser, Firefox by Mozilla, my browser will never put it in its browser history, so the browser will never make the underline purple, which has been set in the CSS as the visited link color. Not all browsers boil down ![]() the same; on my phone, the last visited link is the hover color until I tap something else, then the link loses focus and displays the visited color purple. The Mozilla reference tries its best to keep track of these browser differences.

the same; on my phone, the last visited link is the hover color until I tap something else, then the link loses focus and displays the visited color purple. The Mozilla reference tries its best to keep track of these browser differences.

Website: Publishing

Enter the Twisted World

Server software and the hosts they run on are very diverse. Using JavaScript-based server software provides a smooth experience because you can easily craft HTML, CSS, and JS in JavaScript, which the language was built to do. However, there are some definitive drawbacks to writing code in JavaScript as it was originally intended to only ever run in the browser. I prefer using TypeScript  , which extends JavaScript to make it more like a traditional programming language and addresses these drawbacks. Deno is a growing and promising JavaScript, TypeScript, and WebAssembly runtime, meaning we can use it to run code we write in

, which extends JavaScript to make it more like a traditional programming language and addresses these drawbacks. Deno is a growing and promising JavaScript, TypeScript, and WebAssembly runtime, meaning we can use it to run code we write in .ts files and have it boil down into JS code for clients. Fresh is a set of server software and tools written in TypeScript that we will run using Deno. burst.deno.dev is the name of a computer on the internet that is using Deno to run TypeScript code that listens for website requests and dishes back responses. You can view the public GitHub repo, where the code for this website is stored. Whenever it is updated, GitHub runs a script that packs up all my files and sends them to Deno Deploy. Deno Deploy starts running the code on a computer named burst.deno.dev, and you can connect to it the same way you can connect to deno.dev.

The documentation for Fresh is easy to navigate and short. I recommend checking it out as they explain each step in detail and offer alternative configurations. Here are the minimal steps to get a website up that others can visit, just like this one! ( without the blog or cube![]() )

)

Deno =  & Fresh =

& Fresh =

- First, we have to install Deno. Follow this link for OS-specific instructions. To check if it installed correctly, open a terminal and try:

$ deno -v

- We will use Deno to create a new Fresh Project. A Fresh Project consists of a bunch of TypeScript, most of which is code that listens for and responds to requests provided by Fresh. The rest is the code that crafts each page of the website. Fresh gives you some sample pages, but you’ll eventually want to replace these with your own code. This command will download all the needed Fresh code and put it in a folder you’ll have to name:

$ deno run -A -r https://fresh.deno.dev

- Check out your minimal website by following the link in the command line. You’ll receive your website from your own computer (

host = guest)

host = guest)

$ cd whatever-you-named-it

$ deno task start

- If you want others to be able to visit your website easily, you’ll first need a GitHub account. Then you’ll need to upload your code to Deno Deploy: (follow the link Deno gives you in the command line to see your site on the internet!)

$ deno install -gArf jsr:@deno/deployctl

$ deployctl deploy

Step 4 is also technically optional since there are many free hosting options available on the internet. This means many companies will give you access to a computer that has a URL that can be found on the internet. This is nice because you usually have to pay to put your URL in a public registry that maps names like example.com to actual computers. For example, you can ask the world to connect to your personal computer ![]() for all the files

for all the files ![]()

![]() . There are many ways to host files securely, and Deno Deploy has its limitations as to what it can host, but it is a good introduction to cloud hosting and immediately offers a URL everyone can use easily. If you don’t want to send everyone the default Fresh lemon

. There are many ways to host files securely, and Deno Deploy has its limitations as to what it can host, but it is a good introduction to cloud hosting and immediately offers a URL everyone can use easily. If you don’t want to send everyone the default Fresh lemon index.html, let’s check out how I used Fresh to send you this blog post:

Website: Building

Islands

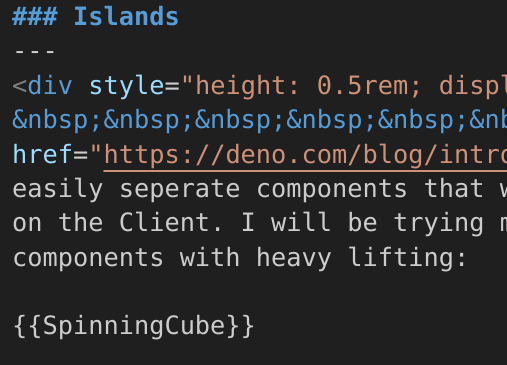

Fresh focuses on a feature called Islands, which makes it easy to specify what code should be run on the server versus the Client. I want to write blog posts like the one you are reading now in Markdown. Markdown is a simple language that simplifies text formatting, like wrapping words with * for italics. This simplicity makes it the preferred language for text posts across the internet; GitHub READMES, ChatGPT Conversations, and Discord Messages all use Markdown. However, I also want to send you non-text content that Markdown cannot describe, like the cube below. For this to work smoothly, I’ll have to convert the Markdown into HTML partially over here and have you fill out the rest over there on an ![]() Island:

Island:

Over here on the server, I’ll focus on getting the static content ![]() (HTML + JS text) ready and delivered while your browser handles the dynamic content

(HTML + JS text) ready and delivered while your browser handles the dynamic content ![]() (running JS). Limiting the server to simple text-processing tasks dramatically affects how fast each page loads since I only have to compute the text to send you before responding, including the code [

(running JS). Limiting the server to simple text-processing tasks dramatically affects how fast each page loads since I only have to compute the text to send you before responding, including the code [ ![]() ] for the cube [

] for the cube [ ![]() ]. I won’t have to run any code to generate the refresh-rate based cube before responding to your browser while navigating here. Your browser will immediately display the static text, and after that, start running the code to display the above SpinningCube as soon as it can.

]. I won’t have to run any code to generate the refresh-rate based cube before responding to your browser while navigating here. Your browser will immediately display the static text, and after that, start running the code to display the above SpinningCube as soon as it can.

Dynamic Routing

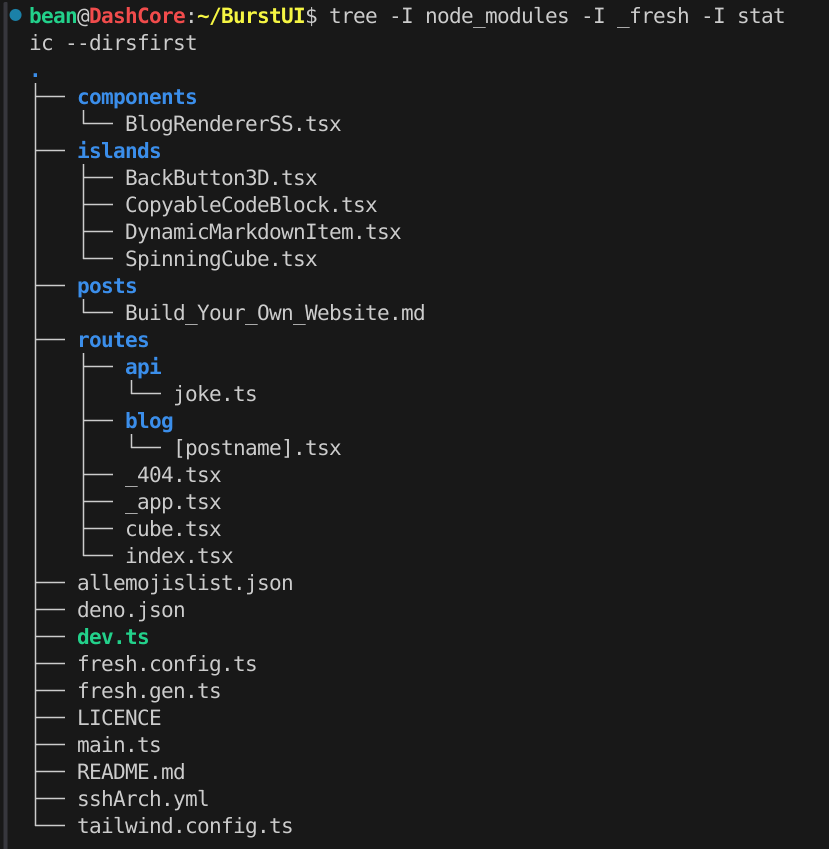

Next, I want to set up a blog system where I can easily make new posts. For now, I have just made a single file in posts called Build_Your_Own_Website.md:

Using dynamic routing, /blog/[postname].tsx will serve [postname].md as HTML when you visit the corresponding /blog/[postname], and if I add another Markdown file in the posts folder for a new link to show up on the homepage & a new route, e.g. /blog/post2 will be generated. Going to a post I haven’t made yet would fail since its corresponding .md file wouldn’t be found by my server resulting in a 404.

Combination - Islands in Blog Posts

![Code Responsible For Building Blog Post Pages: <code>/blog/[postname].tsx</code>](/1/[postname].png)

/blog/[postname].tsx

Above, BlogRendererSS is a Markdown-to-HTML renderer that will run on the server when you request a blog post; turning [postname].md into HTML. DynamicMarkdownItem is an Island that replaces {{ SpinningCube }}’s HTML with the corresponding actual Island’s HTML. This replacement code will run in your browser. The static HTML I sent will come alive and move, having been replaced by the actual HTML and JavaScript code that displays the cube. This twist completes our goal of having a simple but dynamic blogging system that effectively separates Server and Client work. If you want to see exactly how everything is setup postname.tsx,BlogRendererSS.tsx, DynamicMarkdownItem.tsx, and the rest of the files are all on Github.

Using Islands helps build a smooth experience by separating computing resources for specific tasks. For the code blocks above, you get to run the JavaScript code in your browser that copies the text from the website I sent you into your clipboard. I have nothing to do with it. I sent you the text and code that I think you should have. Deciding![]() what to handle locally and what to send can vary depending on the goal; for example, for security, if I bought an API key

what to handle locally and what to send can vary depending on the goal; for example, for security, if I bought an API key ![]() to access

to access Google Maps to show a Street View in a blog post; I could make sure that API connection happens on the server

![]() and not on an Island on the Client

and not on an Island on the Client![]() otherwise anyone could steal the connection details and destroy my wallet with the wonders of elastic pricing. The homepage will load faster if you received the cube here, or this page will load faster if you got the cube there since it is your cube now! You are now in charge of the Cube Island I’ve sent. Try moving the cube across screens with different refresh rates. Your browser will tell the cube to match your monitor’s refresh-rate without needing any help from the server. I am not sending you video frames or animation updates, just sharing the code of it so you use your own GPU to produce your own frames and animations!!!

otherwise anyone could steal the connection details and destroy my wallet with the wonders of elastic pricing. The homepage will load faster if you received the cube here, or this page will load faster if you got the cube there since it is your cube now! You are now in charge of the Cube Island I’ve sent. Try moving the cube across screens with different refresh rates. Your browser will tell the cube to match your monitor’s refresh-rate without needing any help from the server. I am not sending you video frames or animation updates, just sharing the code of it so you use your own GPU to produce your own frames and animations!!! ![]()